Book Review: Clean Sweep by Thomas McKelvey Cleaver

Sometimes a book is so well-written, so comprehensive, and the subject matter so fascinating that any attempt at a book review feels futile. The quality of the book and the length of the review apparently exist in an inverse relationship. “Buy it. The end.”

This is such a book.

However, I doubt Osprey would appreciate that, so let’s dig deeper.

If you’re new to the European air war during WWII or want a book to help organize your brain on the subject, this is the book for you. When I requested it for review over a year ago (sorry, Osprey!), that would have described me. Sure, I was familiar with the general outlines of the war, the concept of air superiority, its importance to the success of a cross-Channel invasion, and the efforts to use strategic bombing to destroy the industrial capacity and civilian morale of Nazi Germany. But that was about it. I knew none of the players except for those still living 80 years later, and didn’t know the tactics beyond a broad, strategic level. This book helped change that. With this book, the reader will learn exciting individual stories and feats of heroism, as well as the facts—from both the Allied and German perspectives.

The stories are what set this book apart from a dry regurgitation of facts, figures, and statistics that could be just as usefully (though not as conveniently) found in after-action reports and official summaries. But few of us want to read that. Instead, Cleaver brings the data and strategy alive by placing the heroes and their deeds squarely within it. For example, you can read or be told that the Eagles—American pilots who slipped through Canada to go fight for Britain before the U.S. joined the war—were determined and gutsy men. But you won’t know it viscerally until you read Cleaver’s detailed description of Don Blakeslee, James Goodson, and the young Greek pilot Spiros Pisanos.

Pisanos was a once-in-a-generation kind of guy. Walter Cronkite, Cleaver tells us, described him as “the single most interesting individual I ever met in all of WWII.” At 16 years old he saw two planes practicing aerobatics, determined this was what he wanted to do with his life, and three years later left for America, having been told that “in Greece, a boy like him could never fly airplanes.” He paid his way by signing up as a cabin boy and planning to “jump ship” when he arrived in the United States. The plan took longer than anticipated because he hadn’t accounted for the fact that there is both a North and a South America. Oops. Undeterred, he eventually arrived in Baltimore, taught himself English by reading the New York Post and a dictionary while commuting to New York City for a job shelling oysters. He enrolled in flight training less than a year after arrival, “padded” his logbook’s 80 hours of flight experience to 300 hours, and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. When the U.S. entered the war, he became the first person to take advantage of a new law which allowed immigrants to gain U.S. citizenship by joining the armed forces, and transferred to the Army Air Force.

See? Now you really know that the Eagles were one-of-a-kind men.

Adding interest, Cleaver sprinkles the stories of Luftwaffe pilots throughout. The book is of course written from the Allied perspective, therefore too much focus on the personal stories of Luftwaffe pilots would threaten to derail the book. Cleaver avoids this trap. Stories of Luftwaffe pilots throughout the book show the effectiveness of Allied strategic bombing, the effects on morale of marauding P-47s and P-51s, and the gradual attrition of Germany’s experienced fighter pilots and their associated replacement by green youngsters willing to bail out at the first sight of tracer fire rather than face seasoned Allied aces.

He also clearly studied German records to provide background and color for his story. For example, as ace Bob Johnson coaxed his crippled P-47 Thunderbolt back across the Channel, an FW-190 pulled alongside him, examined his stricken plane, rocked his wings, and left. Cleaver then tells us that the enemy pilot “was most likely Major Egon Mayer, Gruppenkommandeur of III./JG 2; Mayer reported that he had expended all his cannon ammunition by the time he encountered Johnson, but nevertheless made a claim for the P-47 that was confirmed.” What a great detail! I appreciate the research that was necessary to find those separate action reports, put them together, and not just that, but determine that Mayer received credit for downing Johnson anyway. These are the kinds of details that make Clean Sweep such an excellent book. It’s not just a retelling of a story told in a dozen other books; it’s full of real original research and observations.

But this is hardly a book of individual war stories. At root, it is a technical history of the air war over Europe, and because of this, it offers an excellent springboard for further research. This is hardly surprising—an author capable of unearthing stories like Johnson’s encounter with Mayer would be unlikely to coast on the rest of the book. Combat radius of different fighters, sorties flown per day, kills per day, changing policies within each unit—it’s all here.

At the risk of wandering far afield, I’ll note that this book would be an excellent starting point for studying leadership more generally. Most of the leaders discussed were highly effective in their roles, yet they were invariably different. Very different. Some were quiet, demanding, and focused. Others were bombastic, highly talented aerial gunners, and seemingly frenetic. Not all were what aviators would call “talented” pilots, yet all inspired their men in ways hard to pin down. When they left, whether through promotion or death in action, their units were not the same, and took time to recover. Suffice it to say, I’m left with two new personal heroes to study: Don Blakeslee and “Hub” Zemke.

A review feels incomplete without some point of criticism. But I really don’t have one. The book ably succeeds at being exactly what it is supposed to be: a very objective baseline study of the air war over Europe. I did, at times, find it a little frustrating that Cleaver never engaged in any editorializing on the decisions, men, or battles. Ever. The author himself fades into the background, relates the facts, and leaves the reader to make his own decisions. But I hesitate to mark this as a criticism since Clean Sweep is not that kind of book. It’s history in its purest form, so make of that what you will.

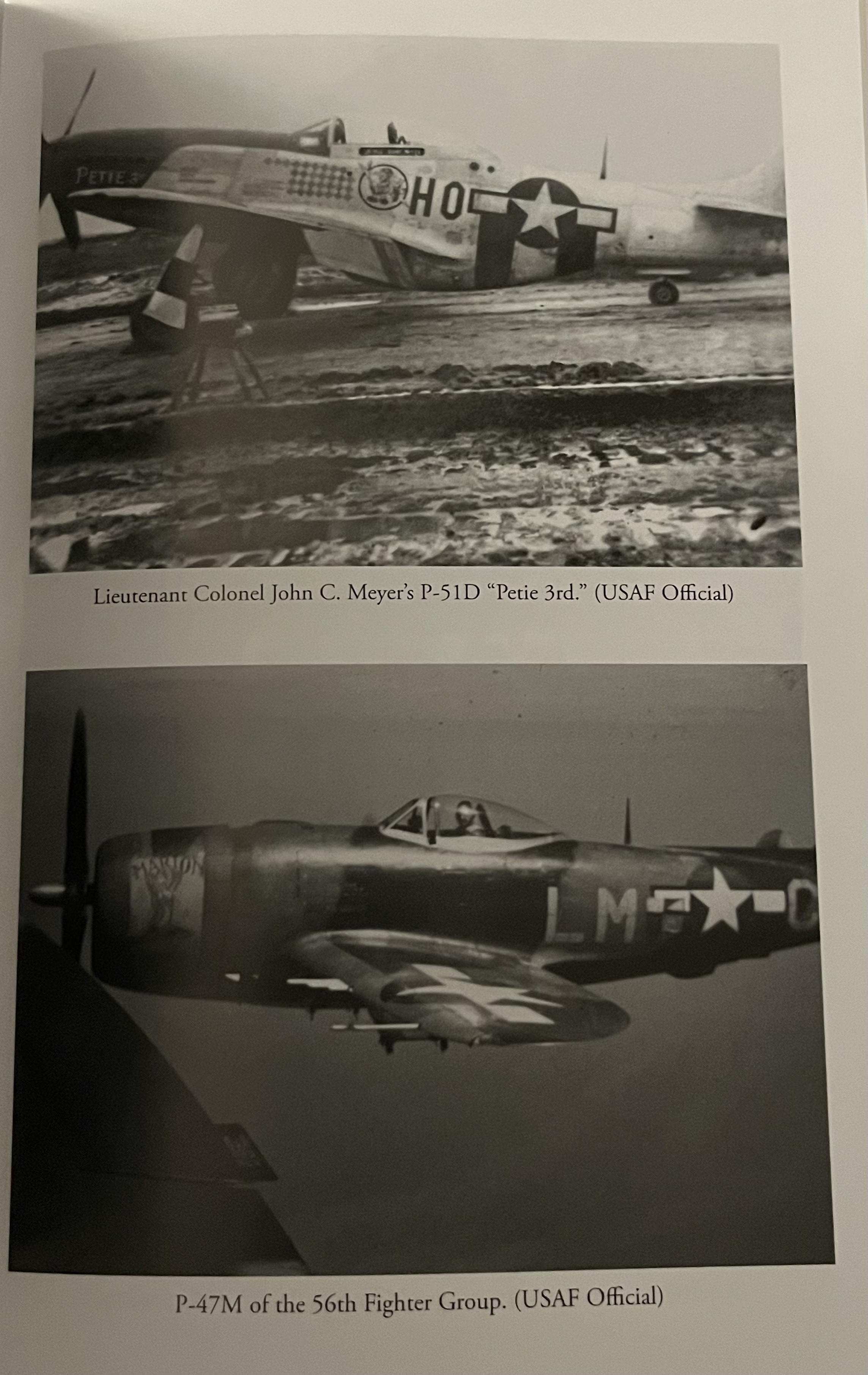

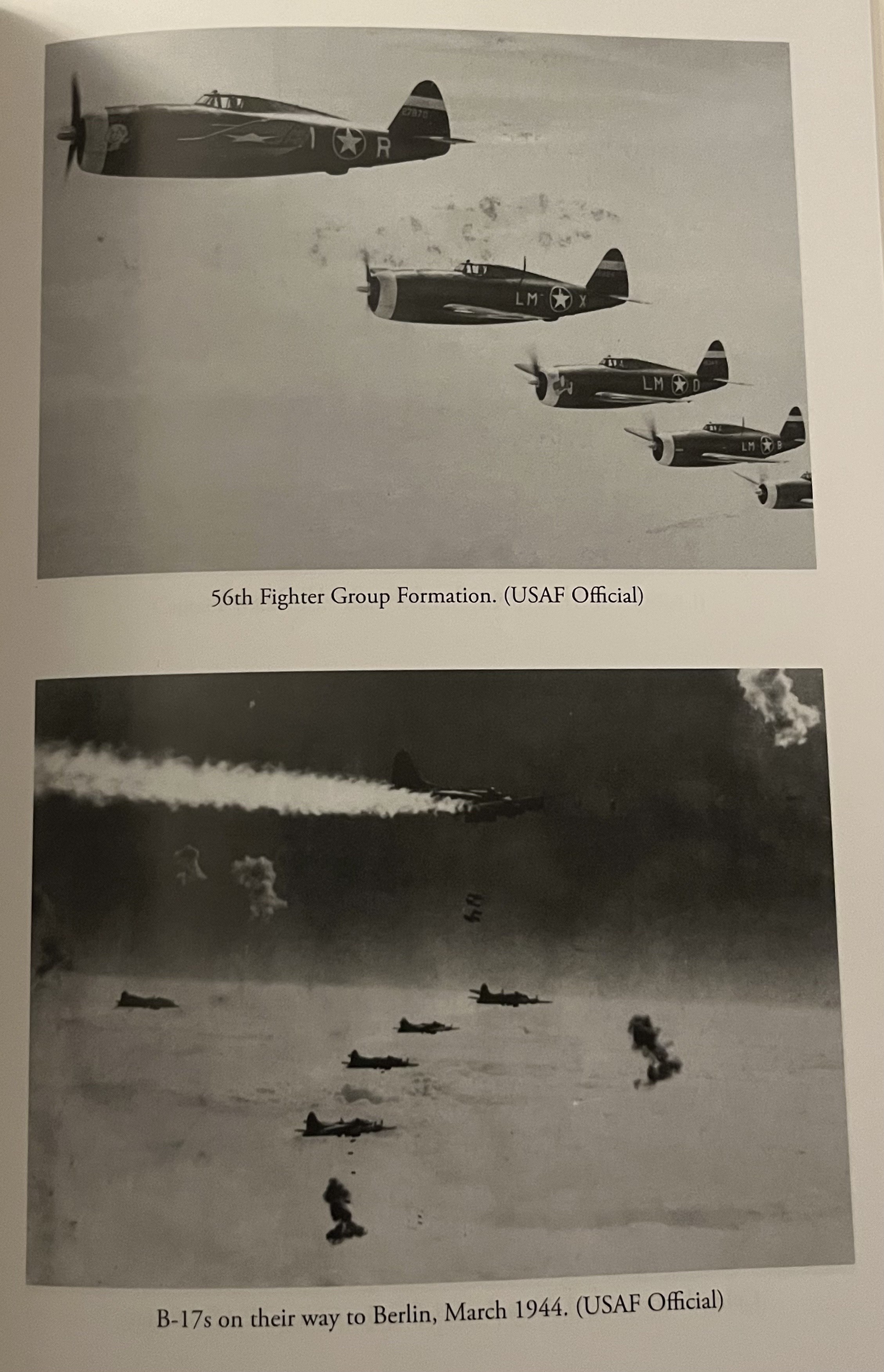

The book is 448 pages divided into 25 chapters with 16 pages of photos in the middle. The chapters are:

1. The Most Important Day

2. War on the Horizon

3. Fledgling Fighters

4. Yanks in the RAF

5. Starting Over

6. Opponents

7. VIII Fighter Command Struggles to Survive

8. The Battle Gets Serious

9. Against the Odds

10. Carrying On

11. Mission 115—The Day the Luftwaffe Won

12. Reinforcement

13. End of the Beginning

14. Jimmy Doolittle Arrives

15. Blakeslee Takes Command

16. One-Man Air Force

17. Big Week

18. “I Knew the Jig Was Up”

19. The Battle of Germany

20. Liberating Europe

21. The Battle of Normandy

22. The Knockout Punch

23. The Road to Bodenplatte

24. Death of the Luftwaffe

25. A Clean Sweep

Author: Thomas McKelvey Cleaver

This book doesn’t just educate; it inspires. I finished and promptly started searching eBay for the autobiographies and unit histories of several groups, particularly the 4th FG. And, perhaps more interesting to this audience, I now know what markings I’m going to use for Eduard’s 1/48 P-51D: why, Don Blakeslee of course!

So, in short, buy this book. You won’t regret it.