Preface

This is another book particularly meaningful to me on a personal level and like Pacific Profiles Vol. 7, Douglas C-47 Series, and I am grateful to the author for writing it. I might have read about Black Sunday in other South Pacific air war books but had forgotten about it - until I flew with a former Fifth Air Force pilot, and then met the son of P-38 pilot and Black Sunday survivor Joe Price. His son loaned me his father's logs and a book about Black Sunday.

As a young freightdog for an air cargo company, I logged around 600 hours in DC-3/C-47s, and many of those flights involved punching straight through thunderstorms. On my first line flight I was flying my first leg and heard Evansville Approach Control calling convective weather to a King Air ahead of us. The King Air accepted a vector away from it. A few minutes later when Approach called the weather to me and offered a vector, remembering all the flight training admonishments to avoid thunderstorms by at least a 20 miles, I happily accepted the vector, certain I had impressed the left-seater. Impressed he was but not to my benefit. He sharply asked what I was doing, took the airplane from me, and told Approach we would continue on course. The expectation was set - we did not run from thunderstorms. Fortunately, we were in a DC-3, and I kept ruminating the belief that there was not a recorded case of a DC-3/C-47 breaking up in flight. Then there was the time with another pilot that we were being beaten up in the bases with intermittent ground contact, and asked for a descent form 4,000 to 3,000. At about 3,500 we entered a violent updraft that resulted in us nose down, floating strapped in our seats, engines idle, landing gear down, approaching the red arc, and "diving" to 4,500! Getting sucked upwards is not as worrisome as getting caught in a downdraft on the lee side of a mountain. Oh, and the flight in a Twin Beech through the outer bands of Hurricane Hugo is memorable, too.

The point of those anecdotes is that nothing I encountered compared with what Fifth Air Force crews experienced, according to one of the captains I frequently flew, Mr. Stan Bagnall. He was a fine gentleman and exceptional airman who had been a Fifth Air Force C-47 pilot over New Guinea and the Philippines. Once when flying with him and voicing displeasure about a few lame bumps, he gave me firsthand insight to New Guinea storms. I do not recall Stan mentioning being involved in Black Sunday but knew our instrument training, aircraft equipment, charts, and navigation facilities access were better than available to most of the Fifth Air Force.

I understand that I have no idea what a South Pacific storm is like and never want to find out, and I can never understand how much awe and respect those pilots deserve. That makes this history of Black Sunday even more incredible to me.

Introduction

Black Sunday - When Weather Claimed the US Fifth Air Force (Second Edition) is a history of a tragedy from Avonmore Books. Authored and illustrated by Michael Claringbould, this fully illustrated 136-page book is catalogued as ISBN 9780645246988. Like so many aerospace disasters before and since, Black Sunday was a series of questionable and outright bad decisions made despite evidence against such decisions. Avonmore writes of this work;

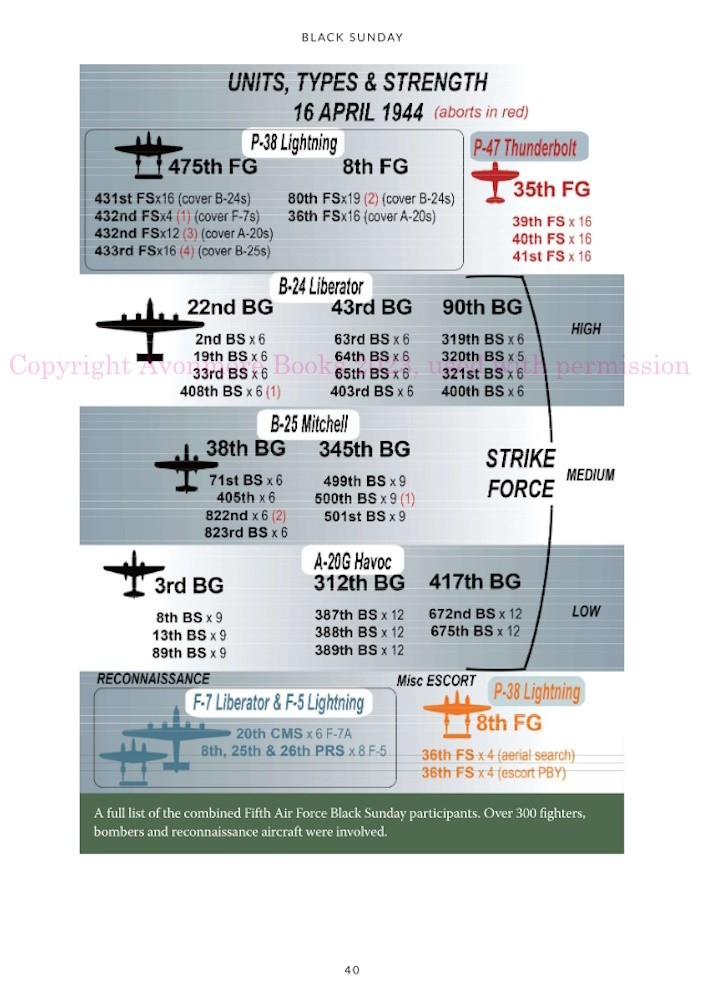

Any USAAF pilot who flew the mission to Hollandia on the fateful afternoon of 16 April 1944 in New Guinea would remember it for the rest of their lives. So would anyone else in the theatre, for the weather-related losses that fateful day earned it the eternal epithet "Black Sunday". The way home for more than three hundred bombers and fighters was blocked by a towering weather front whose thunderstorms rose well above any altitude they could reach. Over enemy territory and caught between mountains and the sea, there was no option but to confront nature.

By dusk that evening 37 aircraft were missing or had been destroyed. A handful of survivors somehow made it back to valley and coastal bases in a series of arduous misadventures. It was, and remains, the biggest non-combat loss of any air force of any nation in the world. More than seven decades later, aircraft from the day are still missing somewhere in the New Guinea jungle.

This major revision to the original version includes dozens of rare photos, complemented by a suite of maps, indexes, and colour profiles of participant aircraft. Japanese diaries reveal the fate of unlucky P-38 pilots forced to bale out. The text liberally cites veteran interviews, post-war wreck surveys and official USAAF records. The narrative tracks down the fate of every aircraft and every crew member, including those who rescued them. Put yourself in the cockpit against nature's massive odds over hostile terrain and watch a composite picture evolve. The accelerating narrative from dozens of different perspectives is both fascinating and overwhelming.

An author of more than 20 other titles, mostly concerning the air war in the South Pacific, Mr. Claringbould has participated in research and even expeditions to crash sites. The seeds for Mr. Claringbould’s passion were planted in 1976 when, "...an irritable priest at Alexishafen, on New Guinea's north coast, reluctantly allowed me to scour and photograph Japanese aircraft wrecks on the mission's land," where he found a Ki-43-II. "Curiosity caused me to start collecting all material on this arcane subject, but it was frustrating. Few publications, including Japanese-language ones, agreed on interpretations..." Thus he began decades of research to learn and clarify, including finding wreckage of downed aircraft.

Now let us proceed with an overview of the tragedy.

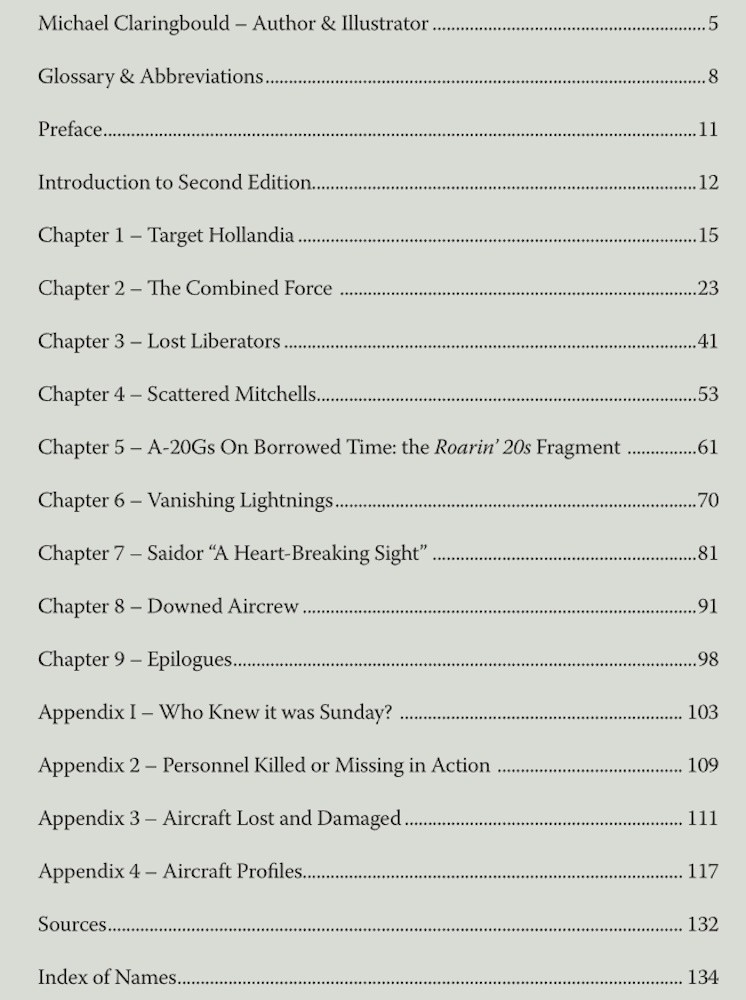

Contents

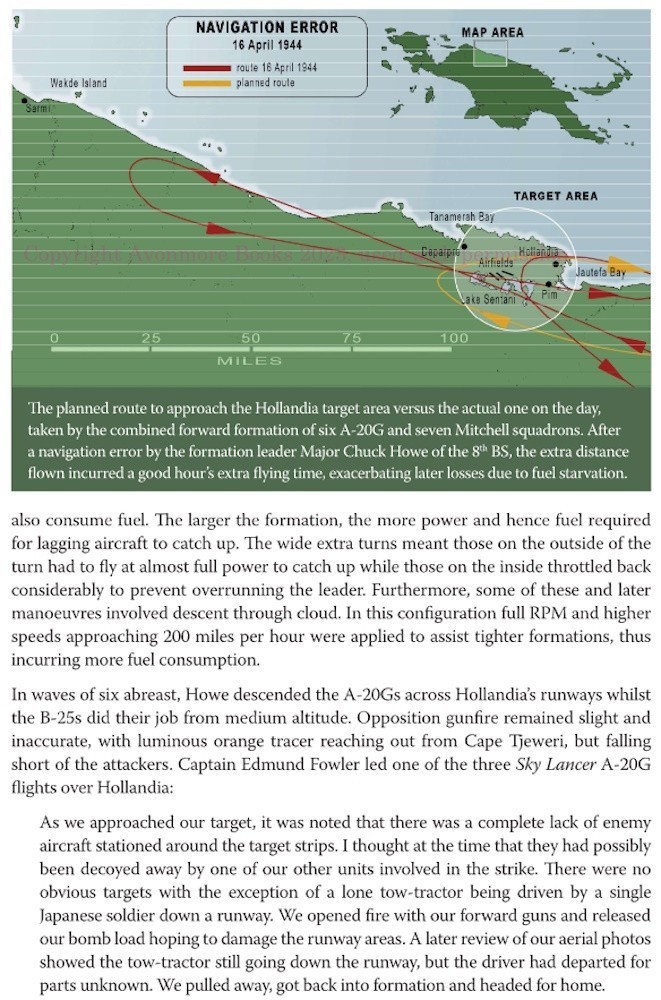

Black Sunday was, and still is, the worst noncombat loss of any Air Force in the world. On that day, the 5th Air Force struck out to attack the Japanese airfield complex at Hollandia. New Guinea weather was already known to be fickle, unpredictable, and could be vicious. And yet high command ordered the mission to go forward, despite increasingly dire reports from weather reconnaissance aircraft. More than 300 bombers and fighters and support aircraft headed out to attack Hollandia. More aircraft were lost that day than during the October-November 1943 raids on Rabaul.

This book describes the mission, using first hand recollections, diaries and reports. It tells how the outbound aircraft saw the worsening weather. It tells of a navigation error which sucked fuel reserves dry. It describes how unknown the topography of New Guinea was, and how unprepared The Fifth Air Force was with few up-to-date maps. Mountain ranges over New Guinea rise up to heights that equal or exceed the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, and yet many of the pilots' maps showed the highest peaks of mountain ranges as being almost a mile lower than they actually were. And despite the level of training our airmen received throughout the war, instrument flight training was not as thorough as once assumed. Consider combining pilots exhausted by a long combat mission, inexperienced with instrument flying, some aircraft types sparsely equipped for instrument flight, encountering some of the worst weather on earth with severe thunderstorms starting just above the treetops with tops billowing up to altitudes where even turbo-supercharged high-performance fighters had trouble reaching. What could possibly go wrong?

The first 40 pages set the stage at the disaster. It relates the weather flights that went out, the conditions they reported back, and the decision to discount the weather pilots' increasing reports of worsening weather. It narrates the outbound mission by aircraft type, i.e., the experience of the B-24s, P-38, A-20s, etc. Then it recounts the attacks on Hollandia.

Now we read about their fight for their lives.

Storms

After the relative safety of the combat mission over Hollandia, the A-20s, B-24s, B-25s and P-38 began to battle for their lives. The storms coalesced into a vicious front that blocked the formations returning to their home 'dromes, stretching off the coast in Japanese territory and arcing west-southwest over mountain ranges, including the Owen Stanleys. Experiences of each force by aircraft type is detailed in unit and individual experiences of trying to avoid, or penetrating, the weather front. Mr. Claringbould, either from participant interviews and records, or personal experience, captures the stress and strain of trying to aviate and navigate while trying to break through the roiling supercharged storm from over enemy territory, most certain to understand that many of their maps were flawed. Many pilot narratives are included, such as this recollection of a P-38 pilot's third attempt to penetrate this storm behind a leader with a defective artificial horizon:

Hello Tomberg...this is Anderson... you are an a spiral to the left. Pick up your left wing. No answer. As the airspeed moved up closer to 300 mph, the balance of the flight stayed in formation. Suddenly the flight swept out into the open in a deep canyon which was completely enshrouded with cloud. Schoener grinned wryly, waved his hand in a goodbye gesture and peeled off to try it alone. Tomberg looked back at my wingman, Joe Price, shrugged his shoulders and started back into the weather again. He really had little choice. The jungle blow was impassable. In addition, it very probably was enemy occupied. His choice was either to try and fly by the seat of his pants or die in the jungle below. Price and I followed Tomberg with grim confidence in his ability is a seasoned pilot, but completely unaware of the true circumstances of his so-called instrument flying. A few minutes later in a tight climbing turn, a P-38 stalled out and he spiraled away. As he did I began calling Tomberg. "Hello Tomberg. This is Anderson. You are stalling me out. You're turning to the left and stalling me ". No answer. Just before I complete stalled, Tomberg's aircraft leveled out, nose downward into another spiral to the left. Once again, the P-38 was proving it was "Lockheed for leadership". The airspeed build up to 375 mph and still going up when the jungle flashed into view. I looked down for a second and saw cockatoos and flowers scattered among the treetops. It was close. Almost instantly after pulling out, we were back in the stuff. My plane suddenly stalled at under 55 inches of mercury and maximum prop RPM, gradually falling off that tight spiral to the right. Carefully, I brought the plane under control begin the delicate operation of flying a fighter on instruments. At the very moment I stalled away, Tomberg released his canopy and bailed out. Japanese or no Japanese, jungle or no jungle, he decided it would be better to get out and walk rather than risk the presence of another cool, green mountain.

A B-25 pilot related:

...the weather was socked in zero-zero. I did not attempt to enter the clouds. I had my flight on the deck from the right wing. The radio is full of desperate calls. In as much of our missions were strafing ones, none of our instruments worked well. We had to use needle and ball almost exclusively. I had very little instrument time. It was tough for aircraft to keep sight of one another.

A B24 crewman:

We entered the front at about 10,000 feet and were on instruments. Shortly thereafter we encountered a fierce downdraft. Control of the aircraft was lost and "Scrappy" directed the crew to bail out. I attempted to do so, but the forces were so great that I couldn't move. I decided I was going to die in the next few seconds. We were suddenly flying straight and level at 200 feet above the ocean. "Scrappy" later recounted at one point the ASI [airspeed indicator] read 400 mph, but took no credit for saving us. Since that mission I became more nervous about the weather than the enemy.

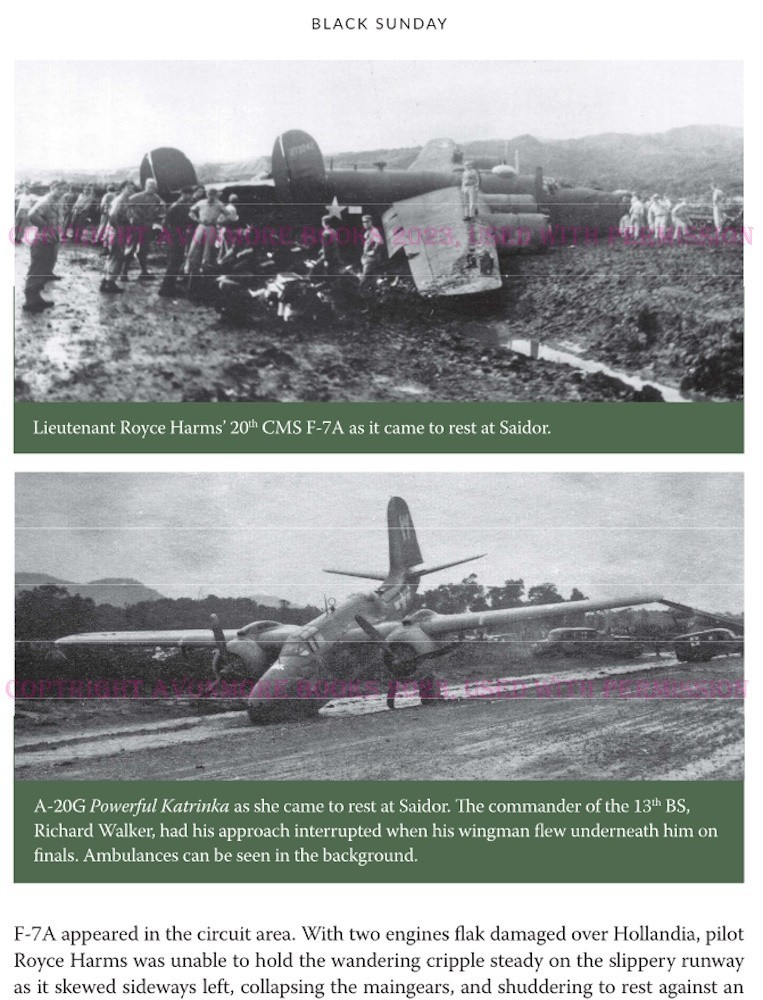

The descriptions of those flights are, for me, as absorbing as accounts of combat missions. The accounts of recovering at Saidor is a story in itself. As are the poignant stories of Downed Aircrew and Epilogue.

Personal accounts and raw numbers enhance the appendices; five pages of Who Knew it was Sunday? was written by Mr. Price:

I ran through the prop wash of another P-38. It was so bad that I thought I'd collided with somebody. I looked around my armor plate to see if my tail booms were still there. It looked okay, but my needle was in one corner and the ball in the other, and my speed was approaching 400 mph. Every move I made to center them was wrong. I knew I didn't have much time. I took my hands of the yoke, my feet off the rudder, undid my shoulder harness and reached for the emergency canopy release. This was what I called an emergency. Just as I started to pull the release the canopy I glanced at the panel. Good 'ol P-38. The needle and ball had centered themselves when I quit fooling around with the controls. Finally I got pulled out of that screaming dive and shortly my airspeed went down to 80 mph. I'd done a complete loop. It must have been a good one without the harness. I had sat tight in my seat all the way through. I milked it through a couple more dives of climbs, got to a level altitude and a steady 200 mph cruise. I was sitting there fat dumb and happy congratulating myself on being able to pull myself out of that mess on needle ball and airspeed, wondering where I was, when to my left there went a P-38 a few feet off my wingtip going straight up. Wait a minute - is he going straight up or straight and level and me going straight down... I put my ear closer to the canopy to check for a build up of wind noise, checked my airspeed again...I had to trust my instruments and just hope I wasn't about to build a big hole.

Within days the survivors were flying missions and braving the weather.

Lt. Price's account is Appendix 1. The others are tables and art.

Photographs, Artwork, Graphics

An exceptional gallery of photographs - many original color - supports the text. Aircraft, airmen, airfields, and other subjects. Modelers can find subjects from that horrible day to recreate.

Appendix 2 is Personnel Killed or Missing in Action, a page-and-a-half table showing:

- Name, rank and position

- Group and squadron

- Aircraft type with serial number

- Status.

Appendix 3 is Aircraft Lost and Damaged, a list in paragraph form of the aircraft with serial number, group and squadron, and tail code. A caption relates information about what happened to the airplane and crew, i.e., P-38 Lieutenant Calvin Wire hit it tree while returning and feathered his right engine but flew into the ocean while attempting a second approach on one engine.

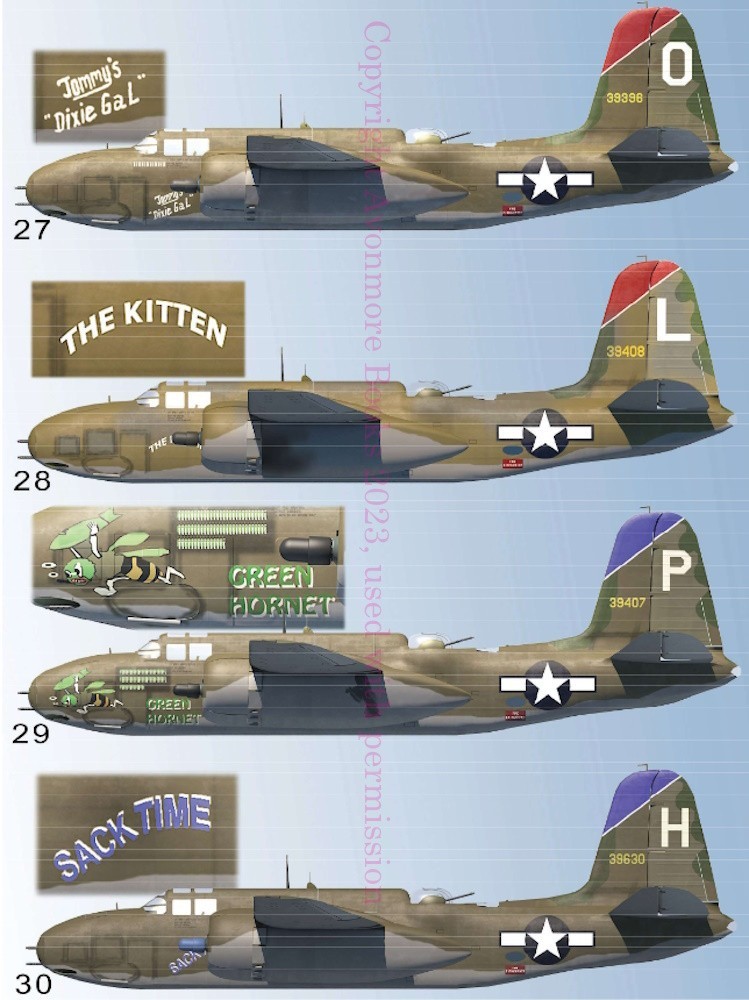

Appendix 4 consists of aircraft profiles:

P-38: eight profiles with eight profiles of the center section; close-up of nose art.

B-25: eight profiles with eight close-ups of nose art

P-47: two profiles

A-20: 12 profiles and 12 closeups

B-24: 10 profiles with six close-ups of nose art

Miscellaneous section:

- P-47

- A-20

- P-39

- Boomerang

- PBY

Each profile is accompanied by a paragraph identifying the aircraft, the unit, and information about the crew, notable colors and markings, and fate of the aircraft.

Further items are:

Map of New Guinea

Page of aircrew quotes

Glossary & Abbreviations

Map of the region over which the Black Sunday disaster occurred, noting airfields and terrain

Illustration of participants of Black Sunday.

Conclusion

During the war, Allied operational losses exceeded combat losses. Black Sunday is a thorough account of the event and presents how dangerous the war was even away from combat. The text is full of engrossing information. Aircrew accounts enhance the text. Artwork and graphics further reinforce the exceptional gallery of photographs.

I find this to be an amazing story and highly recommend it.

Please remember to mention to retailers and Avonmore Books that you saw this product here - on Aeroscale.